In my last metallurgy post, I introduced the experimental concept of nonmetallurgy with my best attempt at producing a sulfur cube. That sulfur cube was fairly decent, however, I was bothered that it had a tan color, because sulfur is supposed to be a bright yellow. The odd color of that cube was due to the fact that the garden sulfur pellets I used were only 90% sulfur, the other 10% being bentonite clay. Once melted, this impure sulfur slurry was opaque and clumpy; it seemed to resemble a muddy puddle.

I mentioned the possibility of attempting to produce a better sulfur cube in that post, and based on the subject of this post, I believe you can infer that I have done precisely that. This time, I used some of my pyrotechnic grade sulfur, which has a minimum purity of 99.5%, according to the manufacturer. Another improvement is that I videoed the entire process this time!

I melted the sulfur using a very similar process to the one that I used last time: I filled a steel can with sand to evenly disperse the heat in hopes that no pockets of sulfur would heat up to its auto ignition temperature. This is crucial because sulfur has a melting point of 235ºF, but its auto ignition temperature, the point at which the sulfur spontaneously ignites, is 450ºF, which is only 215 degrees higher than its melting point. This is a very narrow window, and I absolutely want to avoid burning the sulfur, since burning sulfur has a flame that is virtually invisible — especially in daylight, it produces deadly sulfur oxide gasses, and it is dangerous to extinguish if a stream of water is used, as a strong stream may cause the molten sulfur to splatter or explode, further spreading the nearly invisible fire. These facts, coupled with the notorious stench of sulfur, cause me to be quite uneasy while melting sulfur.

This time, I formed a piece of aluminum foil around my wooden cube stamp and I used the foil as a crucible and a mold simultaneously by placing the shaped foil directly into the sand. I then heated the bottom of the steel can, making sure to move the flame to heat the can fairly evenly; the heat from the can slowly transferred to the sand, which slowly, and evenly, heated the aluminum foil. Once the foil reached the melting point of sulfur, the sulfur powder within the foil began to liquify and collect at the bottom of the foil. I stopped heating the can as soon as I noticed that the sulfur was melting so that I did not overheat it. I allowed the entire system to cool down slowly, but you may notice that I became impatient and I poured some water into the sand to get everything to cool down faster; this is generally a terrible idea, but it worked out fine this time because almost everything had cooled down below the boiling point of water. This would be extremely dangerous if the molten substance was a material that reacts with water, like magnesium, but either way, I do not recommend this technique.

When the sulfur was molten, I was fascinated to note how the sulfur was completely transparent and how the characteristic yellow color had given way to a deep, orange color.

Once the sulfur had eventually cooled down, it had become a cube with interesting, needle-like crystals. I’m not sure what happened, but even though the sulfur had completely cooled, it seemed to maintain a slightly orange color, which tricked me into thinking that it was molten for much longer than it actually was. I also believe that this sulfur cube has even become a little more yellow and opaque and a little less orange and transparent over the last few days. I brainstormed in an attempt to figure out why this is the case, but I can’t think of a logical reason that easily explains this phenomenon. The cube was completely cooled; it’s not that there was molten sulfur left. I also considered oxidation, since metals will typically change color and appearance over time when exposed to air due to oxidation, but when sulfur bonds with oxygen, it forms a gas, therefore, it wouldn’t change the appearance of the surface, other than by roughening it, but sulfur requires heat to bond to oxygen. The only other thing that I can think of is the crystal structure. Perhaps, its crystals don’t form instantaneously upon solidification; maybe the crystals have been slowly forming over time, which might increase the internal surface area, causing it to appear more opaque, similar to the way that the extremely high surface area of powdered sulfur causes the sulfur to look lighter and more opaque. I’m doubting that the crystals form that slowly, and I’m suspecting that it has something to do with the types of crystals formed, maybe the difference between monoclinic and rhombic sulfur. If you know why the sulfur cube changed color over time, please let me know in the comments.

Now that I have produced a relatively pure sulfur cube, even if it isn’t perfect, I’m retiring from sulfur melting for the foreseeable future. Considering the risks and challenges that I face while melting sulfur, I feel quite satisfied with the resulting cube.

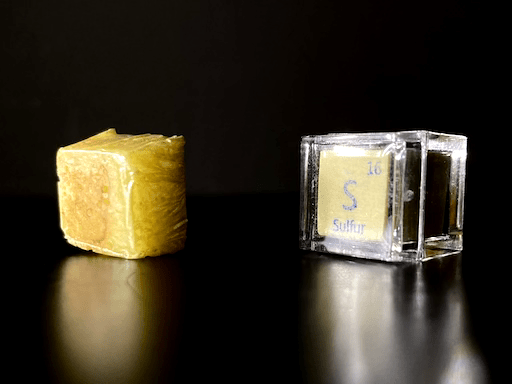

I compared my sulfur cube to a sulfur cube that came from Luciteria, and I found that their appearances strangely differed from each other. My “cube” is also shorter than it should be; this is because I was melting powdered sulfur, and a powder has lots of air space between each tiny particle. I anticipated that the sulfur would shrink greatly when melted, but I underestimated the extent to which it would shrink. Despite this fact, my sulfur cube weighs 2.5 grams, which is oddly greater than the theoretical 2 grams of a Luciteria sulfur cube, but I haven’t weighed my Luciteria sulfur cube because it is too fragile to remove from its case. I am satisfied with my cube in spite of the fact that it is undersized, since this is a very dangerous cube to produce and I am not interested in putting my health at risk again.

Remember, sulfur is a very dangerous element. Consult the Safety Data Sheet for sulfur before handling it. Never burn sulfur and never store it in your house or near humans or animals.

A couple interesting facts about sulfur is that, by mass, sulfur is the 5th most abundant element on the Earth, and it makes up about 2.9% of the entire Earth’s mass; that means there is about 380 sextillion (380,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) pounds of sulfur within the Earth! Sulfur is necessary for the vulcanization of rubber and it is also a necessary element in the human body; about 0.2% of your body’s weight is sulfur, which is about the same percentage as that of sodium and chlorine in your body.

In my opinion, this sulfur cube looks like a piece of pineapple, but others have insisted that it looks like butter.

What do you think my sulfur cube looks like?