In my Elemental Exploration No. 29 post, I had mentioned that I made some Copper (II) Chloride because I thought that this compound would be quite ideal for flame tests, due to the fact that it is composed of nothing more than copper and chlorine — the two ingredients necessary to produce a deep blue flame.

Since writing that post, I have experimented with Copper (II) Chloride and I found that it was practically useless. While the compound does produce a decent blue flame in a flame test, it takes quite a bit of gentle heating to completely dry it, and once it is dry, the brown Anhydrous Copper (II) Chloride quickly becomes green Copper (II) Chloride Dihydrate as it absorbs moisture from the air.

I learned that Copper (II) Chloride is undesirable for most experiments because it is so hygroscopic that it is actually deliquescent.

Hygroscopic Vs. Deliquescent

When a compound readily absorbs moisture from the air and incorporates it into its structure, we call the compound hygroscopic.

When a compound absorbs so much moisture from the air that it dissolves in the water that it absorbs, therefore leaving the compound in a solution that will never evaporate under normal conditions, we call the compound deliquescent.

This deliquescence truly seems to be a problem, especially considering that I have had some Copper (II) Nitrate in solution for nearly half a year, but the water has only evaporated away until the solution apparently reached its maximum concentration for the given conditions, because the solution has remained at that exact volume for several months without change.

Therefore, I was in desperate need of a compound that contains copper and chlorine and is also not deliquescent; that’s when I remembered Copper (I) Chloride — an insoluble solid that only contains copper and chlorine.

Copper (II) Chloride Vs. Copper (I) Chloride

The only factor that changes between the two compounds is the charge of the copper atoms, which determines the structure of the compound and many of its properties.

Simple ionic compounds, such as Copper (II) Chloride and Copper (I) Chloride, consist of a negatively charged ion, known as an anion, and a positively charged ion, known as a cation. For an ionic compound to be stable, the sum of the charges of the anion and cation must equal zero.

In order to find the charge of monatomic ions in an ionic compound, you need to understand the oxidation states of the atom in question. For example, anionic chlorine will always have an oxidation state of -1, meaning its charge is -1, which makes this ion the chloride ion (Cl–). In the case of copper, it is important to note that copper is a transition metal, which means it can have multiple oxidation states; the most common copper oxidation states are +2 and +1, which correspond to a charge of +2 and +1, respectively. Copper ions with a charge of +2 (Cu2+) are known as cupric or Copper (II) ions, while copper ions with a charge of +1 (Cu+) are known as cuprous or Copper (I) ions.

To find the chemical formula of Copper (II) Chloride, you simply need to take a Copper (II) ion and add chloride ions until the charges cancel each other out. Remember, Copper (II) has a charge of +2 and chloride has a charge of -1, therefore, you need 2 chloride ions (Cl–) to cancel out 1 Copper (II) ion (Cu2+) because -2 + 2 = 0. That means Copper (II) Chloride has a chemical formula of CuCl2.

The same thing applies to Copper (I) Chloride, but this time you have Copper (I) ions with a charge of +1 and chloride ions with a charge of -1, therefore, you only need 1 chloride ion (Cl–) to cancel out the 1 Copper (I) ion (Cu+) because -1 + 1 = 0. That means Copper (I) Chloride has a chemical formula of CuCl.

Making Copper (I) Chloride

WARNING: do NOT attempt to make Copper (II) Chloride or Copper (I) Chloride without the appropriate tools and PPE, a firm understanding of the compound’s properties and the properties of every byproduct, and a plan in case of emergency — such as a solution of baking soda in case you need to quickly neutralize any acids.

Like I mentioned in Elemental Exploration No. 29, I used the following balanced chemical reaction to make Copper (II) Chloride (the reactions in this post neglect the water in each compound’s structure):

CuSO4 (aq) + CaCl2 (aq) -> CuCl2 (aq) + CaSO4 (s)

Most of the reactions that people use to convert Copper (II) Chloride to Copper (I) Chloride use many ingredients, most of which are either dangerous or something I don’t have, however, I found a reaction that only takes two ingredients: Copper (II) Chloride and Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C).

I decided to cautiously try this reaction, therefore, I mixed the two ingredients which caused the following reaction to take place:

2 CuCl2 (aq) + C6H8O6 (aq) -> 2 CuCl (s) + C6H6O6 (aq) + 2 HCl (aq)

I filtered out my solid Copper (I) Chloride, but I made sure to wear nitrile gloves because the byproducts of this reaction were dehydroascorbic acid and hydrochloric acid — a strong acid.

I assumed that I successfully converted all my Copper (II) Chloride to Copper (I) Chloride, but after I filtered the Copper (I) Chloride out of the liquid, I added baking soda to the liquid to neutralize the acids in order to make the water safe for disposal, however, I noticed that the colorless liquid became blue, which meant that there was some form of copper remaining in the liquid. I quickly added sodium carbonate to drop the copper out of solution in the form of copper carbonate, which would be a much safer form of the copper, but rather than forming the turquoise precipitate, it formed a brown slurry.

I’m still unsure of what copper compounds were present, however, I collected and dried the brown sludge, which became a whiteish powder that makes me believe it might be more Copper (I) Chloride. Strangely, my filtered sample of Copper (I) Chloride has since turned slightly green, which causes me to think there is some Copper (II) Chloride contamination even though I washed the precipitate very well.

Copper (I) Chloride in Pyrotechnics

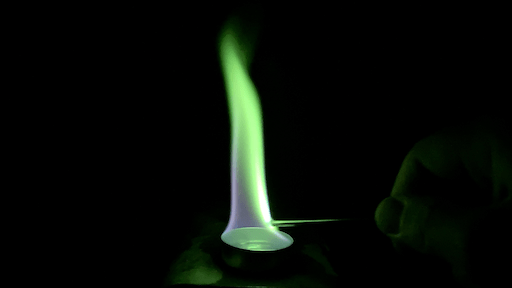

When I used some of my Copper (I) Chloride in a pyrotechnic composition, it produced the most intense blue flame I have seen yet, but the two major problems with that composition are that making Copper (I) Chloride is tedious and inefficient and that the recipe called for both sulfur and perchlorate — which is a dangerous mixture as it could spontaneously combust.

What do you think about Copper (I) Chloride?