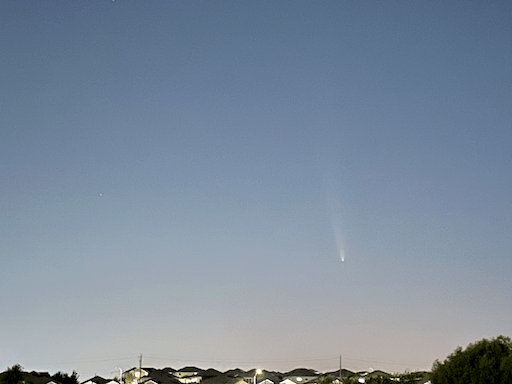

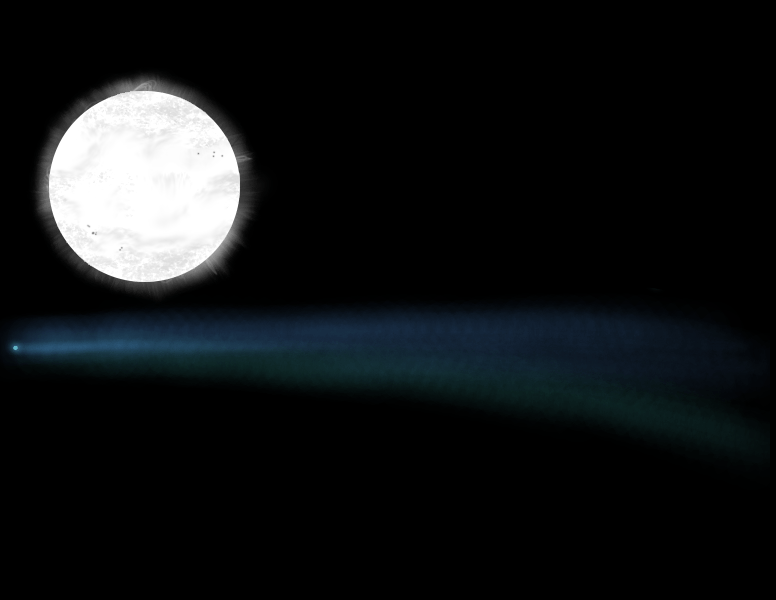

Recently, comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS) flew past the Sun, shining so brightly that it was visible to the naked eye for at least several days. The featured image of this post is one of the images I captured of C/2023 A3 while it was visible to the naked eye.

Comets are small celestial objects made of ice and dust that have a very eccentric orbit around the Sun. Most comets spend the majority of their orbit far away from the Sun, in the dark, icy depths of the outer Solar System; during this portion of their orbit, they have little to no tail and look similar to an asteroid.

When a comet is at or near its perihelion, which is the closest point in its orbit to the Sun, the Sun’s intense heat vaporizes the comet’s icy surface, causing it to jet away from the comet. These jets launch the comet’s vaporized surface, which is now a mixture of gas and dust, into a long line that points away from the Sun; this line of gas and dust is what we see as a comet’s tail. The gas and dust particles in a comet’s tail are minute, in fact, they are not any bigger than smoke particles.

This website has a lot of good information on comets if you want to understand their characteristics better; it even has a detailed image of a comet’s surface toward the bottom of the page that I believe shows its surface jetting away.

Types of Comets

Comets are usually divided into four categories:

- Periodic (comets with an orbital period less than 200 years)

- Non-periodic (comets with an orbital period greater than 1,000 years, but the comet doesn’t have enough velocity to escape the Solar System)

- Comets with no meaningful orbit

- Lost comets (comets not detected during their last perihelion, indicating the comet was either destroyed or its orbit was improperly measured)

Comets are given a name normally beginning with a single letter that specifies which type of comet it is. The letters are P (periodic), C (non-periodic), X (no orbit), or D (lost). These letters are often followed by a number that is the year during which the comet was first observed.

For example, C/2023 A3 is a non-periodic comet that was first imaged in 2023 and 1P/Halley, aka Halley’s Comet, is a periodic comet with an orbital period of only 76 years, which is short for a comet.

While researching C/2023 A3, I discovered a special type of comet called sungrazers, which is a type of comet that flies so close to the Sun that it comes within 850,000 miles of the Sun, which is less than 1% of the distance between the Earth and the Sun; that means sungrazers technically touch the Sun, since the Sun’s corona, the Sun’s upper atmosphere, extends for up to 5 million miles above the solar surface. I also learned that a sungrazer comet, named C/2024 S1 ATLAS, which was only discovered on September 27 was just vaporized on October 28 when flying too close to the Sun. This news article shows a quick time-lapse of the comet’s plummet into the Sun.

Properties of C/2023 A3

When comets are at aphelion, the furthest point from the Sun, they are traveling at their slowest velocity. A non-periodic comet at aphelion should be traveling much more slowly than a periodic comet at aphelion, because a non-periodic comet’s aphelion is much further away from the Sun and its orbit is usually much more eccentric. I believe C/2023 A3 should have been traveling as slow as 0.027 miles per second (96 MPH) at aphelion; that is extremely slow for an object orbiting the Sun. In contrast, C/2023 A3 was measured at 41.8 miles per second (150,000 MPH) at perihelion; that is 0.02% the speed of light.

It is believed that this was C/2023 A3’s first time in the inner Solar System, so scientists are still unsure if the comet will return or if it will be ejected out of the Solar System entirely. If the comet does maintain an orbit, some theorize that its orbital period is only 80,000 years, while others say it took 110 million years to reach perihelion and it will take 235,000 years to return to perihelion — the discrepancy between a comet’s inbound and outbound orbital periods is due to the jets of vaporized surface, which act like thrusters that alter the comet’s velocity and orbit. Either way, the comet could return sometime in the year 82024 or 237024; I will definitely mark that on my calendar.

If you want to see C/2023 A3, you still may be able to, as of November, 2024, but you will likely need a telescope to see it at this point.

A Comet’s Tail

Staring at C/2023 A3 and its long tail made me start to wonder how long a comet’s tail really is. I compared the nearly full moon to my hand at arm’s length and found that its apparent diameter was about the width of my pinky fingernail, which I calculated to be about 0.6º. I then held my hand beside the comet and found that its apparent tail length was about half the length of my index finger, which I calculated to be around 4.7º; that’s quite impressive, especially considering that the comet was 189 times further away from the Earth than the Moon was.

I was initially guessing that a comet’s tail could be a few thousand miles in length, but I soon discovered that a comet’s tail length can range from 600,000 miles to 6 million miles!

Now, 6 million miles doesn’t mean much to me, because we hardly ever measure things that are greater than a few thousand miles on Earth, therefore, I compared that length to other things in an attempt to comprehend this immense scale.

| Unit | Length of a Comet’s Tail |

|---|---|

| Widths of the Contiguous US | 214 to 2,143 |

| Diameters of the Earth | 75 to 750 |

| Diameters of Jupiter | 7 to 70 |

| Diameters of Saturn’s Rings | 3.4 to 34 |

| Distances between the Earth and the Moon | 2.5 to 25 |

| Diameters of the Sun | 0.7 to 7 |

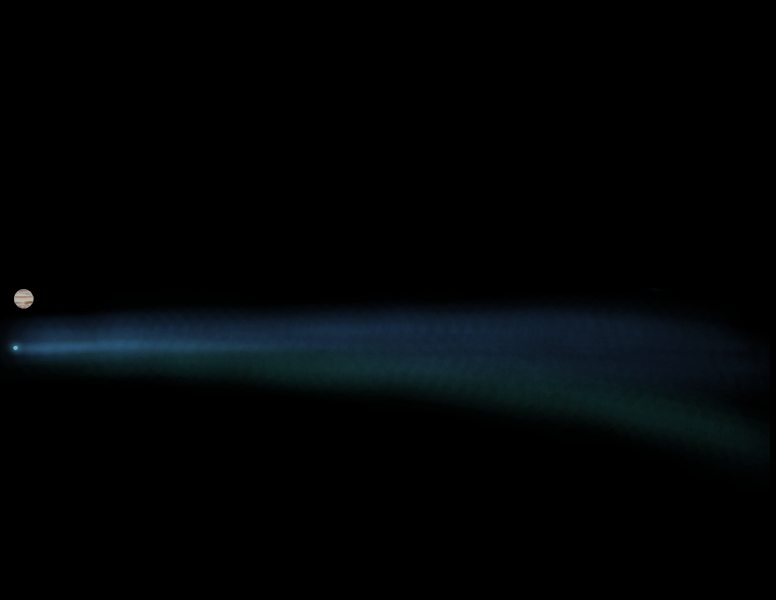

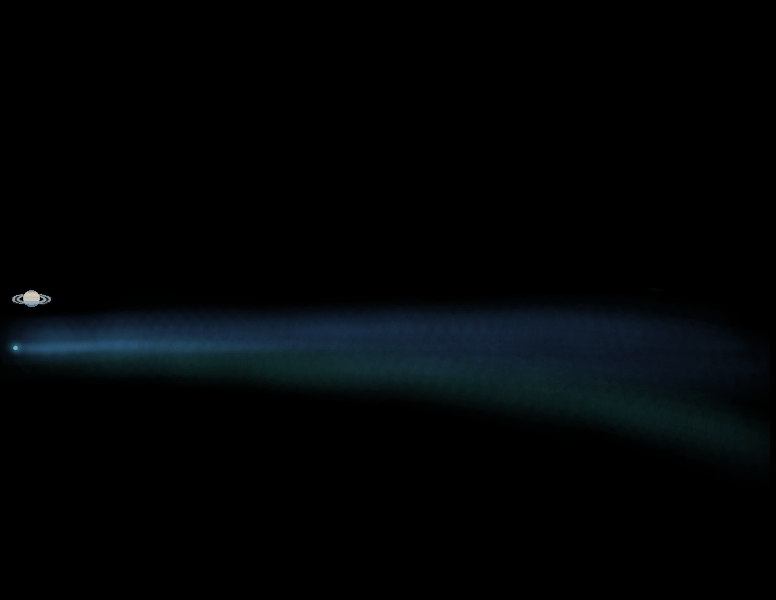

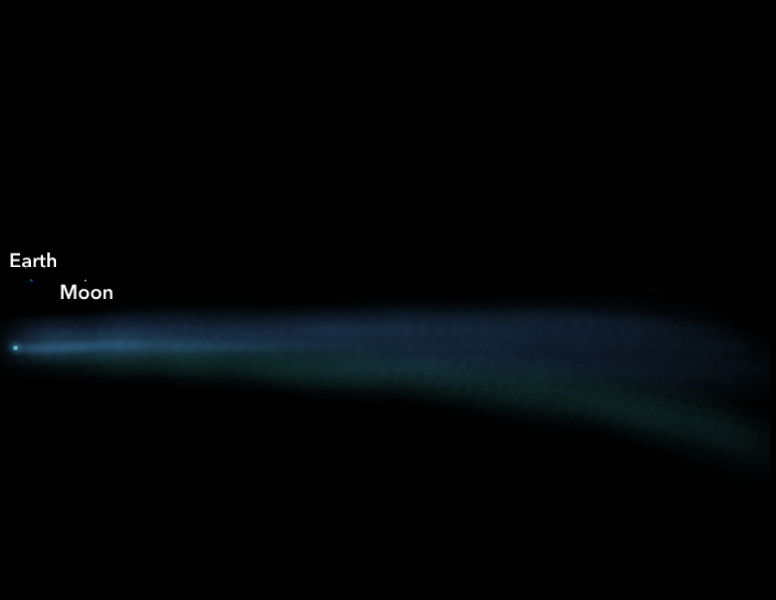

If C/2023 A3’s tail was 4.7º long at the distance that it was during that time (0.4864 AU), then it would suggest that its tail length was 3.7 million miles, but I know my calculations were not perfect, so let’s assume that its tail length was actually the average of the previously mentioned range: 3.3 million miles. Assuming that’s true, here is C/2023 A3’s tail compared to the objects in the previous table.

Origin of C/2023 A3

C/2023 A3 and many other comets are theorized to have originated from the Oort Cloud, a cloud which could contain more than a trillion icy objects that occupy the most distant region in our Solar System. The Oort Cloud is incredibly distant, so much so that it only begins at about 5,000 Astronomical Units (AU), and each Astronomical Unit is approximately equivalent to the distance between the Earth and the Sun, or 92 million miles.

This means that the closer boundary of the Oort Cloud is about 465 billion miles away from the Sun; here is the distance of the inner boundary of the Oort Cloud put into perspective.

| Unit | Distance between the Sun and Inner Oort Cloud |

|---|---|

| Miles | 465 billion |

| AU | 5,000 |

| Distances between Pluto and the Sun | 128 |

| Light Years | 0.08 |

| Distance to Proxima Centauri | 2% |

Notice how the inner Oort Cloud is 2% of the distance to Proxima Centauri, which is the closest star to the Sun. Even though Proxima Centauri is the closest star to the Sun, it is still over 4 light years away.

It’s also important to realize that this is only the closer boundary of the Oort Cloud; the further boundary is said to be 100,000 AU away from the Sun; here is the distance of the outer boundary of the Oort Cloud put into perspective.

| Unit | Distance between the Sun and Inner Oort Cloud |

|---|---|

| Miles | 9 trillion |

| AU | 100,000 |

| Distances between Pluto and the Sun | 2,564 |

| Light Years | 1.6 |

| Distance to Proxima Centauri | 38% |

That’s insane! The far edge of the Oort Cloud is almost closer to Proxima Centauri than it is to the Sun! If my math is correct, the Sun should have an apparent magnitude of -1.6 at the far edge of the Oort Cloud, in other words, the Sun would look about as bright from the outer edge of the Oort Cloud as the star Sirius does from Earth. Compare that to the Sun’s magnitude as seen from the Earth (-26.8) or from C/2023 A3 during its perihelion (about -29.3); keep in mind that a magnitude increase of 5 is roughly equivalent to 100 times dimmer, whereas a decrease of 5 means about 100 times brighter.

This may be irrelevant information, but I just thought that the colossal scale of the Oort Cloud was worth mentioning. The entire volume of the Oort Cloud, minus the volume of space before the Oort Cloud begins, is an absurd 3 duodecillion cubic miles, meaning 3 followed by 39 zeros (3,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 cubic miles)! That is 10 octillion times the volume of the Earth, 10 sextillion times the volume of the Sun, or 13 trillion times the volume of UY Scuti — the largest known star, which is so big, that if it was in the Solar System, it would almost reach from the Sun to Uranus. The volume of the Oort Cloud is large enough that if each of the 8.2 billion people on Earth owned 1 billion car dealerships that each had all of the cars on Earth (1.5 billion cars) and each of those cars had a garage the size of the Earth, all of the garages would fit within the Oort Cloud with space to spare, in fact, the leftover space is still enough for each of those 8.2 billion dealership owners to have a house the size of 79 UY Scutis or 59 billion Suns, and even then there would still be plenty of extra space.

Hopefully this example helps you grasp just how far away C/2023 A3 ventures during its long journey into the distant reaches of the Solar System.

What is your favorite comet?