Whenever you decide to cast an object in metal, you first have to choose a metal that works with your capabilities. If you ever look at the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements, like I frequently do, then you might realize that most of the elements out there are metals, in fact, 79% of the 108 elements with known properties are metals. Maybe this sounds a bit unrelated, but what I’m trying to say is that most of the fundamental materials that things can be made of are metals, therefore you have a large selection of metals from which to choose. The fact that these metals can be combined together, which is called an alloy, into practically any combination and concentration means that there are nearly limitless metals and alloys at your disposal.

The only problem is that some of these metals are toxic, some are too reactive, and some are radioactive. So how do we know which metal is the best to choose? Well, you could look online to see what metals many people use for casting, however, we could also look at some graphs to compare the properties of different metals to determine which one best suit you.

We will be looking at 22 metals; each metal will be represented by its symbol, which is in parentheses, on the graphs if it is an element and not an alloy. These metals are:

- Aluminum (Al)

- Bismuth (Bi)

- Brass

- Bronze

- Chromium (Cr)

- Cobalt (Co)

- Copper (Cu)

- Gallium (Ga)

- Gold (Au)

- Indium (In)

- Lead (Pb)

- Magnesium (Mg)

- Nickel (Ni)

- Pewter

- Platinum (Pt)

- Silver (Ag)

- Sodium (Na)

- Steel

- Tin (Sn)

- Titanium (Ti)

- Tungsten ( W )

- Zinc (Zn)

There are many variations for each of the 4 alloys that I have included, however, for these statistics, I will be considering brass to be yellow brass, bronze to be aluminum bronze, and steel to be low carbon steel. Another thing to keep in mind is that most available sources of aluminum are really aluminum alloys, but I’m only looking at statistics for pure aluminum.

If you wish to melt pewter, I beg you to either buy bulk pewter from a good source or mix your own blend of tin, antimony, copper, and bismuth. Please do not destroy history by melting pewterware or tinware, as this form of art is no longer in production. Just think about the people long ago who spent their time crafting this art.

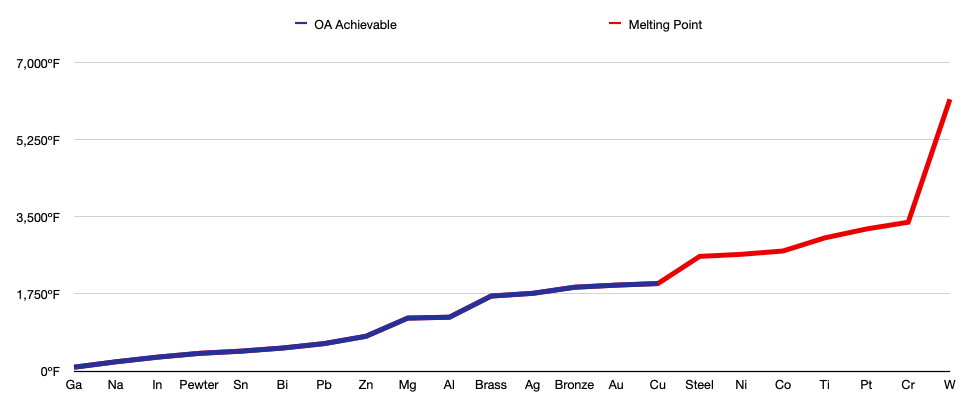

Each metal will be ranked based on its properties, but the most ideal metal will be determined based on my specific needs, for example, I won’t be using any metals with a melting point above 2,000ºF at this point in time. Maybe you have a furnace that can surpass these temperatures, in which case you will have to take your needs into account.

For obvious reasons, I’m excluding highly toxic metals and all radioactive metals. Well, technically bismuth is a radioactive metal, but its half life is about 20 quintillion (20,000,000,000,000,000,000) years, which makes the metal’s radioactivity so weak that scientists hadn’t detected its radioactivity until 2003. Bismuth is often considered a stable element, and it’s safe enough that I am completely comfortable with melting it; its half life is 16 billion times longer than that of the primary source of radiation from the human body (potassium-40), which means you are many times more radioactive than the typical sample of bismuth.

There are 5 major properties that I will be considering for each metal: melting point, price, reactivity, hardness, and toxicity.

Keep in mind that these numbers and statistics are approximations to provide a decent representation of each metal’s characteristics; if a high level of accuracy is crucial for the success of your project, then do not rely on these numbers.

Melting Point

One of the first things to consider about a metal is its melting point. You could have the most ideal metal possible, but it does you no good if you cannot reach its melting point; all you would produce is a hot chunk of metal.

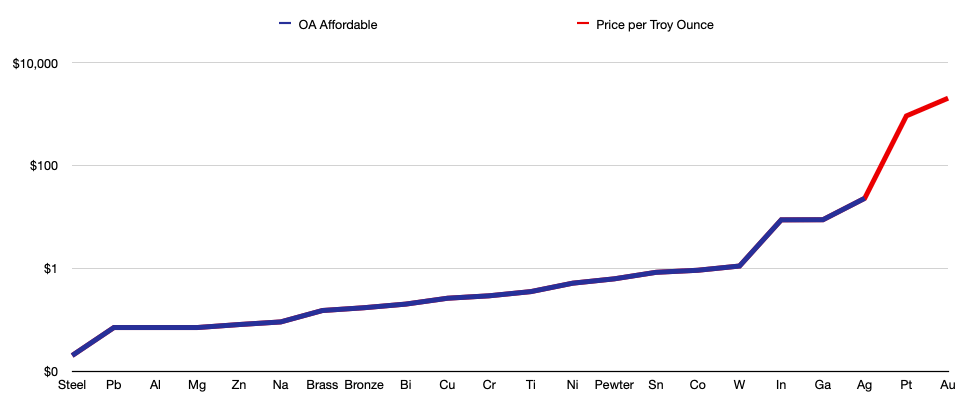

Price

These prices are only estimates, as the monetary value of a material can fluctuate by the hour, besides the fact that you will likely pay more depending on the source and quality. This is a very important thing to take into account for a small scale metallurgist, since finances are not exactly infinite.

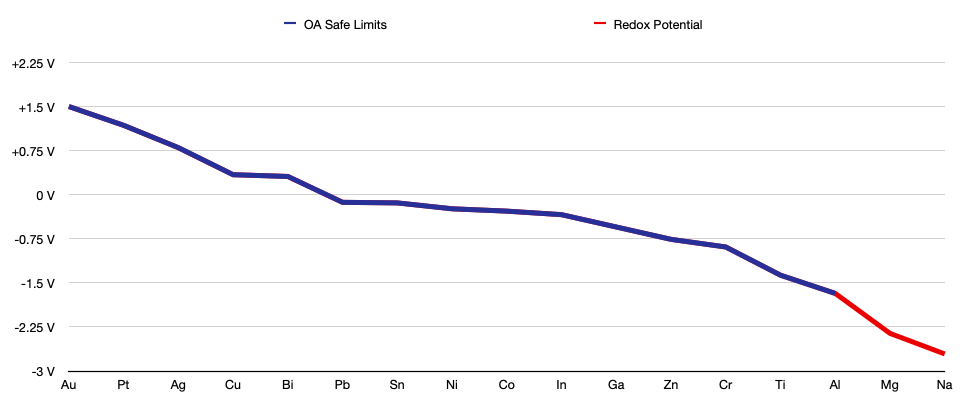

Reactivity

The following is a list of the metals and the degree of their reactivity; the further down the list, the less reactive a metal is. This list can give you an idea of how dangerous each metal is and which fluids to keep away from the metal.

I didn’t bother consulting this list before I started melting aluminum, and then I wondered why my aluminum oxidized so severely every time I quenched it. When I finally looked at this list, I realized this issue was likely due to the fact that aluminum reacts with steam, which was formed when the water boiled off the surface of the aluminum. I knew that sodium became explosive in water, but thankfully I learned this lesson with aluminum before I decided to try it with magnesium. Learn from my mistake and resist the urge to quench certain metals in water, even if it makes a cool sound.

Do not quench metals in water if they react with water.

Reacts with Cold Water

- Sodium (Na)

Reacts Slowly with Cold Water, Rapidly with Boiling Water, and Vigorously with Acids

- Magnesium (Mg)

Reacts with Steam and Acids

- Aluminum (Al)

Reacts with Concentrated Mineral Acid

- Titanium (Ti)

Reacts with Acids, Poorly with Steam

- Zinc (Zn)

- Chromium (Cr)

- Cobalt (Co)

- Nickel (Ni)

- Tin (Sn)

- Lead (Pb)

Reacts Slowly with Air

- Copper (Cu)

May React with Some Strong Oxidizing Acids

- Bismuth (Bi)

- Tungsten ( W )

- Silver (Ag)

- Gold (Au)

- Platinum (Pt)

Hardness

The hardness of a metal determines its likelihood to be scratched or deformed. The harder a material becomes, the less likely that it will lose its shape, however, if the hardness is too great, the material usually becomes quite brittle and is then susceptible to shattering. For example, think of a material with a very low hardness as being similar to clay, but a harder material as being more similar to glass. Currently, I will avoid working with any metals that are either too soft or too brittle.

I’m using the Mohs Hardness Scale, in which 1 is the softest and 10 is the hardest. For reference, talc has a hardness of 1, and diamond has a hardness of 10.

Toxicity

Again, these values are all estimations and averages; the toxicity of each metal depends on concentration. Another thing to consider is that each metal has its own list of things with which it will react under certain conditions. These reactions produce new compounds that have their own toxicity; if a metal reacts with oxygen, it will form oxides, if it reacts with CO2, it can form carbonates, and if it reacts with water, it will produce hydroxides. Hopefully you understand that this topic can be quite complex. The best thing to do is research each metal and its properties before you work with it, but this list can help point you to less toxic metals.

In this list, I’m only considering these metals in their metallic form and not the numerous compounds that they can form, but their ranking is a little subjective. This is by no means an accurate ranking of toxicity, but rather a general categorization.

This does produce a slight bias that makes some metals — such as cobalt, copper, magnesium, and sodium — appear as if they are completely toxic metals, but these are actually necessary elements in your body; how is this possible? Well, we all know that oxygen gas (O2) is crucial for most life, but did you know that breathing single oxygen atoms (O) would be fatal? This is because the necessary elements for life are only beneficial in the correct forms and concentrations.

Relatively Harmless

- Gold

- Platinum

- Silver

- Steel

- Tin

- Zinc

Practically Nontoxic

- Bismuth

- Brass

- Bronze

- Magnesium

- Pewter

- Tungsten

Slightly Toxic

- Aluminum

- Chromium

- Cobalt

- Copper

- Gallium

- Indium

- Magnesium

- Nickel

- Titanium

Moderately Toxic

- Lead

- Sodium

One more thing to consider is that, while brass is decently harmless, I would never allow a new metallurgist to melt brass, because it is quite dangerous to melt. Its melting point is over 1,700ºF, which is above the boiling point of zinc (one of the metals in brass). This combination can cause the brass to violently splatter and produce toxic zinc fumes, which you certainly want to avoid inhaling.

The Most Ideal Metal

By assigning 0 to 3 points to each metal that rank its ideality in each category, I can then compare the metals by their overall score. I will also entirely remove any metals that are unachievable or dangerous; this reduces our selection to 10 metals.

So there we have it; for my current capabilities, it appears that these metals are the most reasonable, but bismuth, pewter, tin, and zinc appear to be the four metals that best suit me. I will be keeping these metals in mind; maybe they will soon make an appearance in this metallurgy series.

What metal do you like the most?

Onward American 🇺🇸

Source: Melting Points of Elements