I recently discovered that I have a passion for metallurgy. Some of you may have gotten the clue from my 100th post where I shared 100 ways to cook a grilled cheese sandwich, if you recall method number 51.

The question is how did I get a charcoal furnace and how do I know that it can exceed 1,200ºF? We will get to that in a moment, but let’s start with how I got into this unique art of fire and metal.

The Caveman Kid

When I was a child, I discovered fire and how useful it can be. Ok, I didn’t actually discover fire, but I learned a lot about it from the countless campfires I built and enjoyed each summer. It could be said that I went through a caveman stage in my life, as I was often known for experimenting with fire. Well, if you asked anyone else, they would say I was “playing with fire.”

I continued to perfect my fire starting skills while testing new methods for building fires throughout my teenage years. As time went on, I became increasingly more confident in my ability to handle fires, but I was also simultaneously expanding upon a different, inherent fascination of mine.

Metal Collections

Another phenomenon that began during my childhood was my collecting of items, particularly metallic ones. I began by observing and appreciating pennies, nickels, dimes, and quarters, but then I was introduced to foreign currency when I was given Mexican peso coins.

I continued collecting currency, but at some point, there was a split in my collection. Not only did I collect money, but I also began to seize any scrap metal available to me, such as copper and aluminum wire, scrap lead, and rusty pieces of steel.

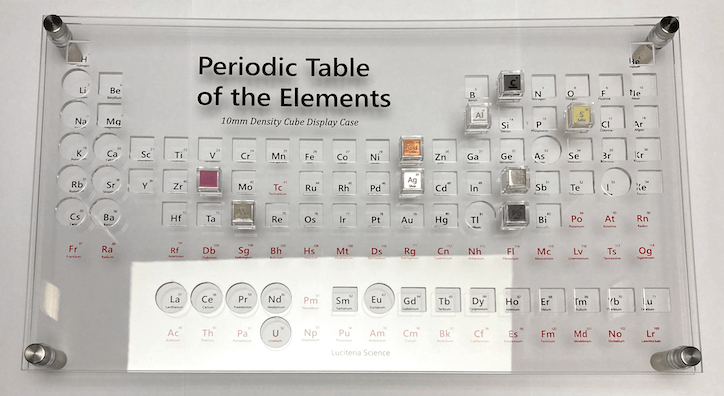

This scrap collection eventually came to a halt when I learned about Luciteria’s pure element cubes, which not only perfectly matched my love for collecting metals, but also my deep interest in chemistry. I am still collecting these element cubes to this day.

In hindsight, it’s evident that I have always had an inexplicable fascination with metal, but it wasn’t apparent to me until a while later when I discovered a new passion.

When Fire Meets Metal

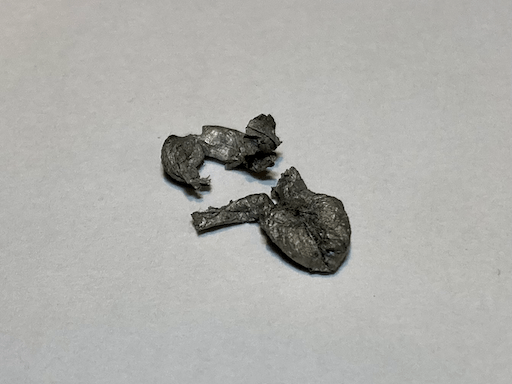

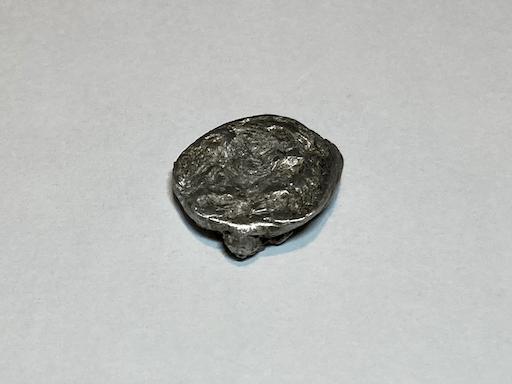

For several years, I had watched videos of people melting aluminum and I thought it might be fun to do someday, but I never really thought it was possible that I could melt metals myself. That all changed in early 2023, when I had acquired a handful of scrap lead pellets, which I was originally going to throw away, but one day when I was looking down at the pile of lead, the sudden realization occurred to me that lead has a low melting point. I then racked my brain to find a way to melt it; finally, after months of planning, I went ahead and built a very rudimentary foundry.

I found a relatively safe patch of ground outside to work on, I cut a La Croix can in half for a crude crucible, a crudecible if you will, and attached copper wire as a handle. I carved my mold out of a scrap piece of drywall with a hole saw, chisel, and nail. This foundry cost me a whopping $0!

I placed my lead into the crucible and used a propane torch to melt the lead. Once it was fully liquified, I poured the lead into the mold and waited for it to cool.

I would definitely not recommend trying this for yourself, since there are several dangers, besides the obvious danger of hot metal: heating lead to a liquid state can cause it to release lead fumes, which are quite harmful to inhale; exposing molten lead to aluminum causes the lead to soak into the aluminum, forming an extremely brittle alloy, which caused my thin walled, aluminum crucible to crumble within a matter of minutes; and using drywall to mold anything hotter than about 200ºF can cause splattering. This is because drywall is mostly made from gypsum, which is chemically known as calcium sulfate dihydrate; the dihydrate indicates that there are 2 water molecules in gypsum crystals for each calcium sulfate. When the temperature of gypsum surpasses 200ºF, the water within the crystals begins to vaporize. These escaping steam bubbles can make your molten metal splatter in severe cases; not only could this harm you, your property, or bystanders, but this will also ruin the clarity of your cast.

Despite the dangers and rudimentary nature of my foundry, I managed to cast my first ever coin. I did have to recast my coin once because of the previously mentioned water vapor issue, but it was an almost perfect success.

Foundry Version Two

Months after my first success, I found myself being a caveman again and experimenting with the smoldering embers from a campfire. I noticed how much heat came from the dimly glowing coals, and how they flared up when I blew on them. I then remembered the correlation between temperature and the emitted color of matter. Just like any good scientific caveman, I realized that because I could make the coals glow bright orange, which meant that they were somewhere around 1,800ºF, I could theoretically melt aluminum on them.

I threw a small piece of aluminum onto the coals, but I was frustrated to see that the aluminum didn’t form a shiny puddle; instead, it severely oxidized. This happened because molten aluminum is quite reactive and I was literally blowing oxygen onto the reactive aluminum when I was trying to fuel the coals. I realized that I needed some type of metal container to hold my molten aluminum while protecting it from oxygen, which just turned out to be a crucible; rather than learn from my last melt, I reinvented the crucible. I’m not sure why the word crucible never crossed my mind that night, maybe the lead fumes were messing with my brain. I’m joking, of course, I was in a well ventilated area, aka outside, and I was also upwind of the lead; I research and take precautions before starting any project.

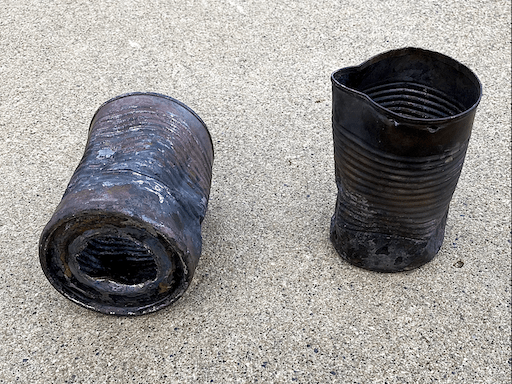

When disposing of a couple steel cans, I noticed how a smaller can nested inside a larger one. I then cut a hole for an air intake in the large can, grabbed an old pipe, scavenged a fan out of an old space heater, and grabbed several handfuls of charcoal that survived the fire. By filling the large can with charcoal, igniting the charcoal, and blowing air into the hole in the large can with my fan, I was able to heat the crucible on the coals. Shortly after that, both cans began to glow a furious orange.

This furnace also cost me a hefty $0 to build, but it was significantly more dangerous than the last foundry.

After several attempts, I was finally able to metal aluminum, but my casts up to this day have been unimpressive. I even tried and failed to melt brass and copper with this furnace.

Another downside of this furnace is that because the cans are not stainless steel, they will eventually rust until they disintegrate. I did have two sets of cans rust away.

Foundry Version Three

This Christmas, I received a gift that is an official furnace from a family member. This new furnace uses either propane or MAPP gas as fuel, and unlike all of my previous furnaces, it is insulated. It supposedly can reach more than 2,000ºF, therefore I should be able to melt a much more broad selection of metals.

I have not fired up the new furnace yet, but I will return to this series soon and share my new experiences with this furnace.

In total, I managed to perform about a dozen melts with varying levels of success in the year 2023, however, 2024 just might be the year when I finally produce a decent coin, but this time it could be copper or even something a bit more valuable… you will have to keep an eye out for more posts in this metallurgy series.

What are your thoughts about metallurgy?